Internment Camp

Between 24 April 1945 and 1 December 1948, Camp Westerbork was used as an internment camp for members of the NSB, SS and others suspected of collaboration with the Nazis. After the Second World War, between 120,000 and 180,000 people were interned in over 120 internment camps in the Netherlands.

Van gevangene naar bewaker

Internment Camp Westerbork (Interneringskamp Westerbork in Dutch) was one of the most peculiar camps. When the first ‘bad’ people came into the camp, 850 Jews still ‘lived’ in the camp. A large share of them, who had to live with the constant tension of possibly being transported to ‘the East’, were employed as guards for the interned in the first months of liberation.

This included Ed van Thijn, who was ten years old at the time. ‘I had to go into the woods with members of the NSB, to gather firewood. These people moved like ghosts – at least, to my recollection – and begged me for food. I did not yield to them. Although I had a stick, they could have easily overpowered me. They did not. I think I could have taken them. They were so weakened. They only had basic needs, haggard from hunger. It was a very absurd situation.’

In the summer of 1945, the circumstances in Internment Camp Westerbork were chaotic. Aside from the Jews, there were the guards of the Dutch Internal Forces, the former resistance, and a few representatives of the Military Authority (Militair Gezag, MG) who contested each other for power. Partly because of this, life was characterised by poor circumstances and (incidental) psychological and physical abuse. At least 89 of the interned died within the first four months in Westerbork.

In September 1945, there was improvement in daily life in the camp. Resulting from a number of far-reaching measures within security and with the departure of the final former Jewish prisoners, the chaos in the camp disappeared. The changes had a positive impact on the interned.

As of the fall of 1945, a visitation and mail scheme was established. From that moment on, it was permitted to send and receive a letter – which was heavily monitored in advance – once a month, and once every four weeks, two loved ones were allowed to visit.

Willy Munneke-van Polen, a child of ‘bad’ parents, on that period: ‘When my mother knew where my father was, she took the bike to Westerbork as soon as possible. She wanted to see him. Soon after, a visitation arrangement was established and she could visit him once a month. She didn’t skip once, even though the circumstances were miserable.’

Re-education and re-integration

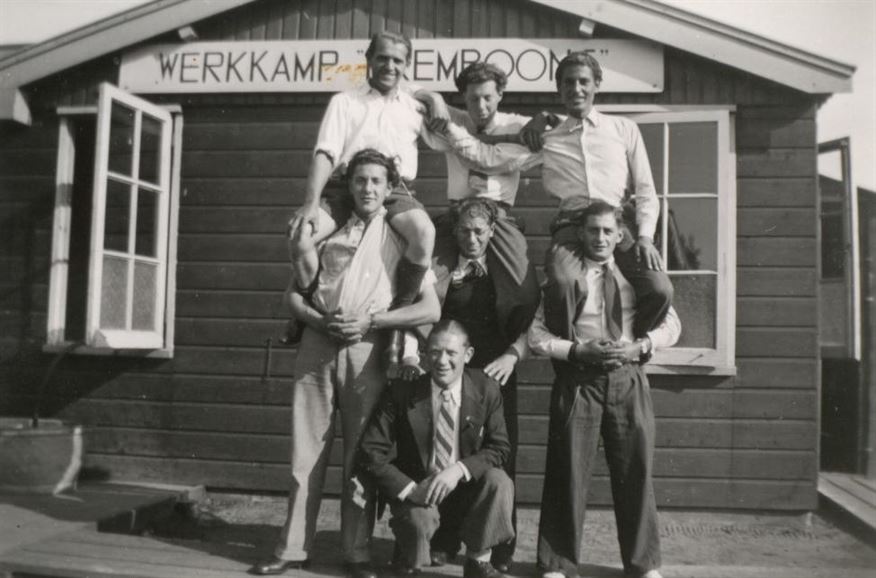

On 1 January 1946, the Directorate-General for Special Jurisdiction (Directoraat-Generaal voor de Bijzondere Rechtspleging, DGBR) took over the care for the ‘bad’ Dutch. The character of the camps changed: more focus on re-education and re-integration of people, and less on punishment. The social living conditions improved, in part thanks to the theatre performances, radio reception, sports, and a library. The psychological living conditions, on the other hand, worsened, mostly because it took long before people were put on trial and/or released.

In the last year (1948), the status of Internment Camp Westerbork changed. As a result of the high costs, the government decided to have most people return home. An exodus of the camps followed: in one and a half years, the number of interned decreased with more than 70,000.

‘Severe cases’

Those who remained in Westerbork were so-called ‘severe cases’: NSB mayors, ‘bad’ police officers, and (mostly) Dutch Waffen-SS members. They had to deal with bad conditions. The barracks were missing furniture, windows, and even floors after years of heavy use. The toilets were downright disgusting.

Op 1 December 1948, the camp closed its gates. The majority of the interned who were left could go home. There was no question of a truly felt freedom, though. Many of the interned concluded that the war had really started for them on 5 May 1945: with the liberation, they lost all physical, material, and social freedom. Subsequently, internment deprived them of their mental freedom.

On 15 April 1947, Anneke Brouwers’ father was released. Two weeks before that, he wrote to his family. ‘I have noted down the bus timetable well. You should see whether you’ll be able to pick me up. I will leave out of the gate around 11 o’clock. Heavily loaded with two suitcases and a pack of blankets. It’s just a sigh now. I cannot imagine yet that I will just be with you again. The circumstances have changed, though. No home, no furniture, no position. We will try to build a new future.’