The Westerborkfilm

In the spring of 1944, camp prisoner Rudolf Breslauer made film recordings in Camp Westerbork at a large scale. He did this at the assignment of German camp authorities. Commander Albert Gemmeker in particular appeared a major proponent of making a film about life in the camp. The intention was to edit together a professional film with the recordings. It didn’t get that far, though. After a couple of months, they stopped filming and a definitive final version was never made. A lot of raw material has been preserved, and many aspects of Camp Westerbork are visible on it.

The ‘Westerborkfilm’ is rightly considered as an irreplacable, unique illustrative document that has been given a special place amid all sources about the Second World War. Rightfully so, because there is no similar film footage of any Nazi concentration camp. The film and production documents have been included in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. Subsequently, the unique footage has been researched, selected, and carefully restored.

Fundamental objection

The first recordings of the Westerborkfilm took place on 5 March 1944. The set was the registration barrack, where a Christian church service for converted Jews was taking place. It led to a riot: two pastors of the Gruppe Protestanten, Srul Tabaksblat and Max Enker, appeared to have fundamental objections to the recordings. Furious, they left the space. Gemmeker responded fiercely: both men were locked into the punishment barracks for weeks and removed from all positions. Only the interference of the Protestant Church prevented them from being deported.

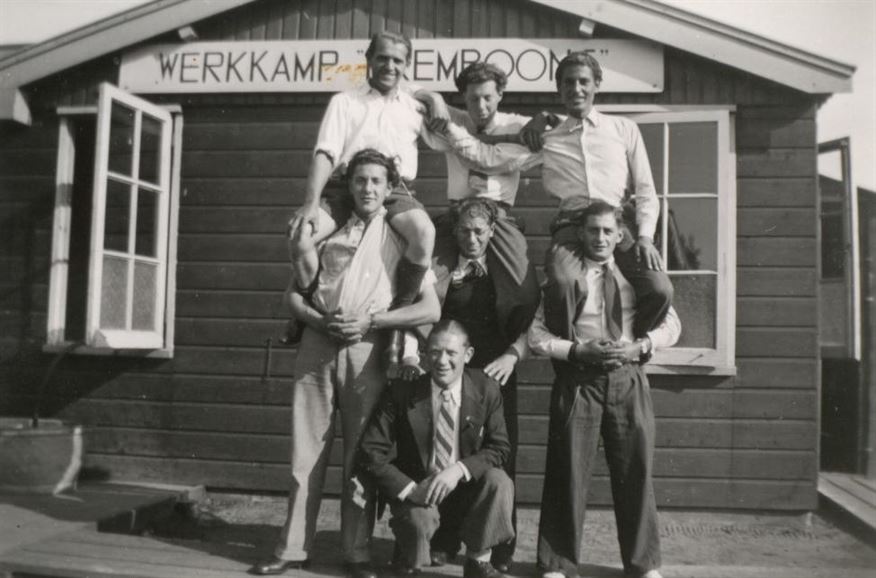

The footage shot by Breslauer showed the daily life in the camp: an outgoing transport, an incoming transport, the registration and a cabaret performance, working on the greenhouse in the camp commander’s garden, morning gymnastics, working in the toy factory and working in the airplane wreck yard.

After Rudolf Breslauer was taken away in September 1944, his colleague Wim Loeb made it his task to finish editing the film. Thanks to a marriage to a non-Jewish woman, he was exempted from deportation. In a makeshift studio in his camp residence, Loeb made two draft versions of the Westerborkfilm: an ‘official’ one and a ‘rest version’. The first montage was intended for Gemmeker. The ‘rest version’ was smuggled out of the camp as evidence and housed with a notary in Amsterdam.

Briefly before and after the liberation, the other recordings of the Westerborkfilm found their way outside of the camp. After a long journey, they arrived at the archives of Beeld en Geluid (together with the ‘rest version’), where they were restored masterfully.

Symbol of the Holocaust

In the years after the liberation, the Westerborkfilm was an important source for historical research and imaging. It was used as evidence during the trials of the Nazis, added to documentaries and exhibitions, and it was the subject of academic discissions. The images of the departing transport in particular became a symbol of the Holocaust the world over. The most famous image was the girl looking out from between the wagon doors. Only in the nineties would it become clear to whom this ‘face of the past’ belonged.