Transports

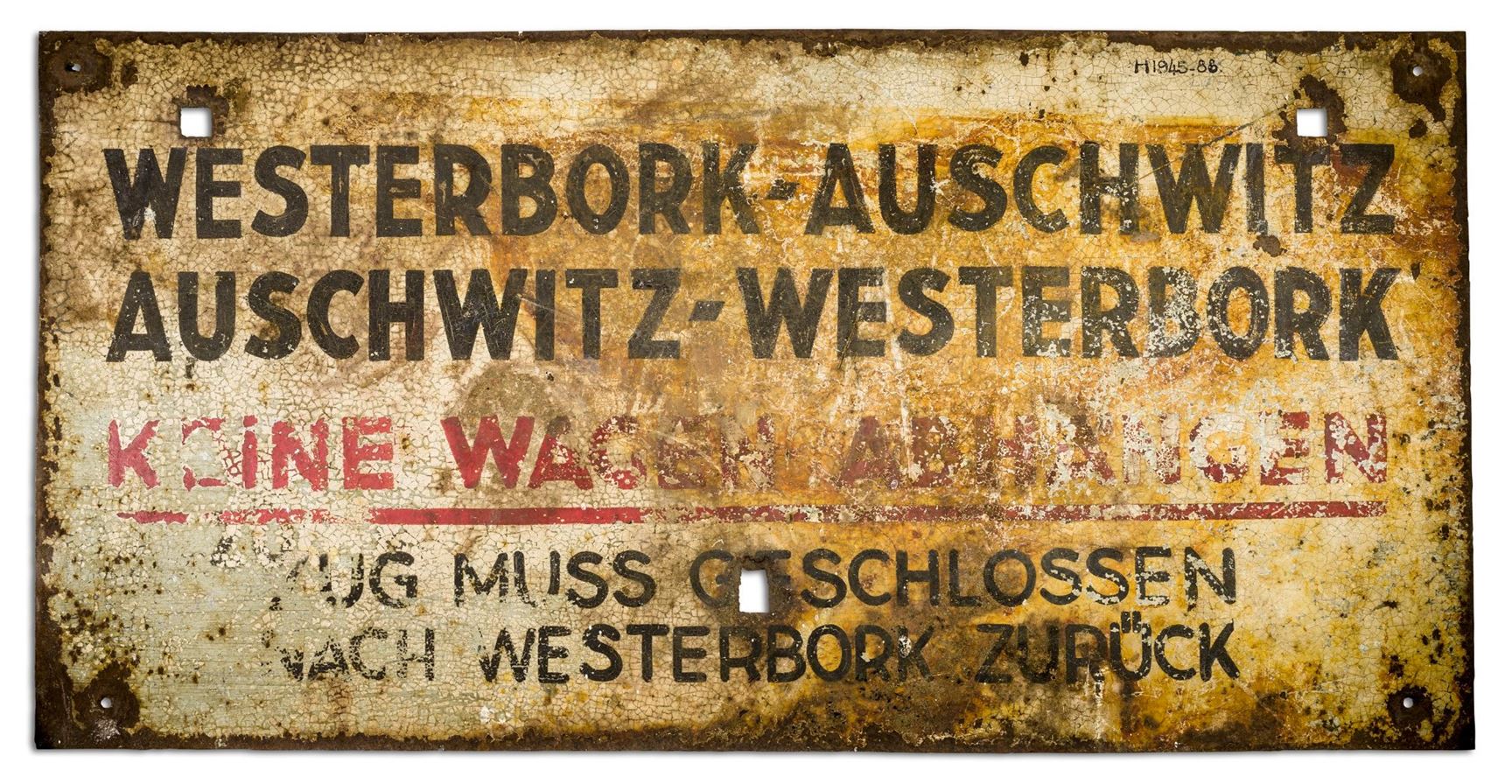

More than 100 trains departed from Camp Westerbork in the direction of the camps in Eastern and Mid-Europe. On 15 and 16 July 1942, the first prisoners were deported to Auschwitz. 2,030 Jews, amongst which a number of orphan children. The start of a long line of victims. In the first months, the train departed twice a week: on Monday and Friday. In 1943, Tuesday was most frequently the day of transport. Prior to every transport, the prisoners who had to go were selected. The selection was a matter for the camp commander, who gladly passed on the task to the Jewish employees of the camp administration.

The fatal day

The numbers were determined in Berlin. There, Adolf Eichmann reigned as the head of the department IV B 4 of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt. He arranged the deportation of millions of Jews and tasked the SD in Den Haag to remove the desired number of Jews from our country. Here, Sturmbannführer Zöpf arranged everything with Westerbork. Up until the fatal day, it was uncertain who had to leave. From 1943 onwards, it was made known who had to get ready to travel per barrack. Whoever heard their name knew what they had to do. They would grab their belongings in the same suitcase, backpack, or duffel bag they had taken with them on their travel to Camp Westerbork. Then they would head to the Boulevard des Misères, the main road of the camp next to which the tracks were laid, where a long train was waiting. For the ones who had to leave, a suffocating tension had come to a sorry ending. For the families who were pulled apart, an uncertain goodbye followed.

The sliding doors are closing

All the SS had to do was watch. Gemmeker, too, saw to his enjoyment how wonderfully the Westerbork system worked. He had everything prepared to the letter. If the group was very large, the members of the Fliegende Kolonne knew what to do. They helped the last in line get on and pushed as long as it took for everyone and their luggage to get inside. Then, they would close the sliding doors. Everyone was counted quickly. That numbers was passed on through one of the two small windows in the wagon. The man of the OD chalked it in big numbers on the outside, so it could be ascertained whether everyone was still there at their arrival. There hardly was an opportunity to escape. With the exception of two small, barred windows, the wagons were shut tight. After an elongated whistling, the train started moving choppily. Most trains left the Netherlands via Hooghalen, Assen, Hoogezand, Sappemeer, Zuidbroek, Winschoten, and Nieuweschans.

From transport to transport

The prisoners of Camp Westerbork lived from transport to transport. That lasted until 13 September 1944. Then, the last big train with 279 people left for Bergen-Belsen. Amongst them, there were 77 children who were captured on their hiding addresses. Almost 107,000 Jews have been taken away to ‘the East’ largely through Westerbork. In addition, 247 Sinti and Roma and a few dozen resistance fighters were taken. Most trains went to Auschwitz. Other transports had Sobibor, Theresienstadt, and Bergen-Belsen as their destination. A much smaller number went to the camps Buchenwald and Ravensbrück. In total, only 5,000 people returned.