Return and Reception

In the first months of 1945, the concentration camps in Eastern Europe were liberated. There were very few Dutch Jews still alive. In early 1945, the Russian army freed 854 emaciated Dutch prisoners in Auschwitz-Brikenau and 18 survivors in Sobibor. In April of that year, 1,800 prisoners from Bergen-Belsen were found on a train in Tröbitz and another 200 Dutch Jews from the same camp were discovered in Magdeburg. In early May, about 2,000 Jews were liberated from Theresienstadt. Several hundred Jewish prisoners were liberated from other smaller camps in Eastern Europe.

The Jewish inmates initially greeted the liberation with disbelief. In many camps, most people did not realise they were free. Only hunger, cold and exhaustion dominated their thoughts. When it became possible, prisoners started a search for food, but the camp survivors only had a few weeks to recuperate. The anger took the upper hand; a lack of transport, poor roads and a lack of communication led to delays in their return to the Netherlands. Dutch aid for victims started later than for survivors from other countries.

Return

Many liberated Jews left the camps on foot. Some did not want to wait for organized transport. Others could not bear the thought of another night in a concentration camp. On their return to the Netherlands, the homecoming Jews were in for a big disappointment. The Dutch people had little time for the camp survivors and the government acted very formally and in a bureaucratic way. The tragic past of the inmates was not taken into account, the rules for them were the same as for anyone else. Some Dutch people even were anti-Semitic to the returning Jews. Auschwitz survivor Ab Caransa waited a few weeks after arriving and then visited his previous employer. He asked for an advance, but it was in vain. “Why? All that time you had shelter and food.”

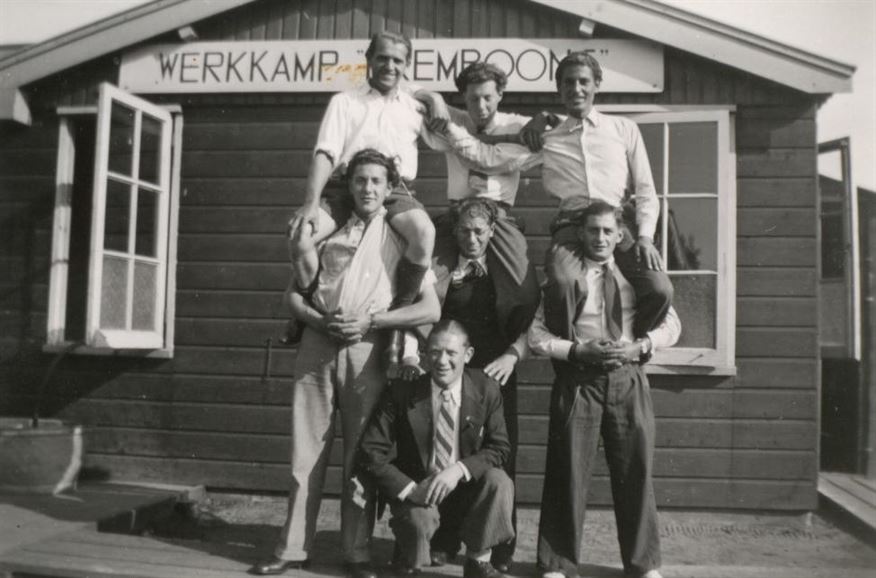

Most Jews arriving in the Netherlands were initially sent to repatriation camps. Some had to go to camps where members of the NSB were imprisoned. No distinction was made between them and the prisoners. Other Jews went looking for their former possessions, but there were not many to be found. Houses were frequently occupied by other non-Jewish families and their contents were either redistributed or sold.

The Jewish Community after 1945

Of the approximately 140,000 Jews who lived in the Netherlands around 1940, 30,000 survived the Second World War. Their world was a very different one from that of the non-Jewish Dutch. As if the loss of (sometimes all of) their relatives and friends and the lack of a sociable environment was not enough, many had lost their homes, their work and their possessions. The long experience of fear, humiliation, disease, cold, hunger and exhaustion brought many of them to breaking point.

Nearly 5,000 Jews decided to emigrate shortly after the liberation. For the people who stayed behind, there was almost no Jewish community left intact. Most had lost a teacher or pastor and in most places the synagogues had been destroyed.

Many Jewish people withdrew to a safer environment. They no longer wanted to belong to a Jewish community. According to a census in 1960, of the 25,000 Jews in the Netherlands, only 15,000 belonged to a Jewish community. Ten years later, this number had decreased to less than 5,000. It was only in the course of the 1960s that the long silence came to an end.

It was broken by the trial in Jerusalem of the Nazi bureaucrat Adolf Eichmann, the monumental television series ‘The Occupation of Dr. L de Jong’, the book ‘The Collapse of Jacques Presser’, and the debate surrounding the release of the ‘Drie van Breda’ (‘The Breda Three’), the last three German war criminals captured in the Netherlands. During the sixties and seventies of the last century, the suffering and violation of the Jewish communities reappeared.