Arrival

In 1951, camp Westerbork was given its next function: residential settlement for a couple thousand Moluccans.

From generation to generation, Moluccan men served in the KNIL, the Royal Netherlands-Indies Army (Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger). They were loyal to the colonial power and the queen. As such, they fought on the Dutch side on the Second World War, and subsequently against the Indonesian nationalists. When the Republic of Indonesia became independent in 1949, the dissolution of the KNIL followed. However, as a result of the struggle for independence on the Moluccans that had broken out then, it was impossible to demobilise the soldiers of Moluccan descent on Ambon. It was decided that those with family members were brought to the Netherlands to settle there temporarily.

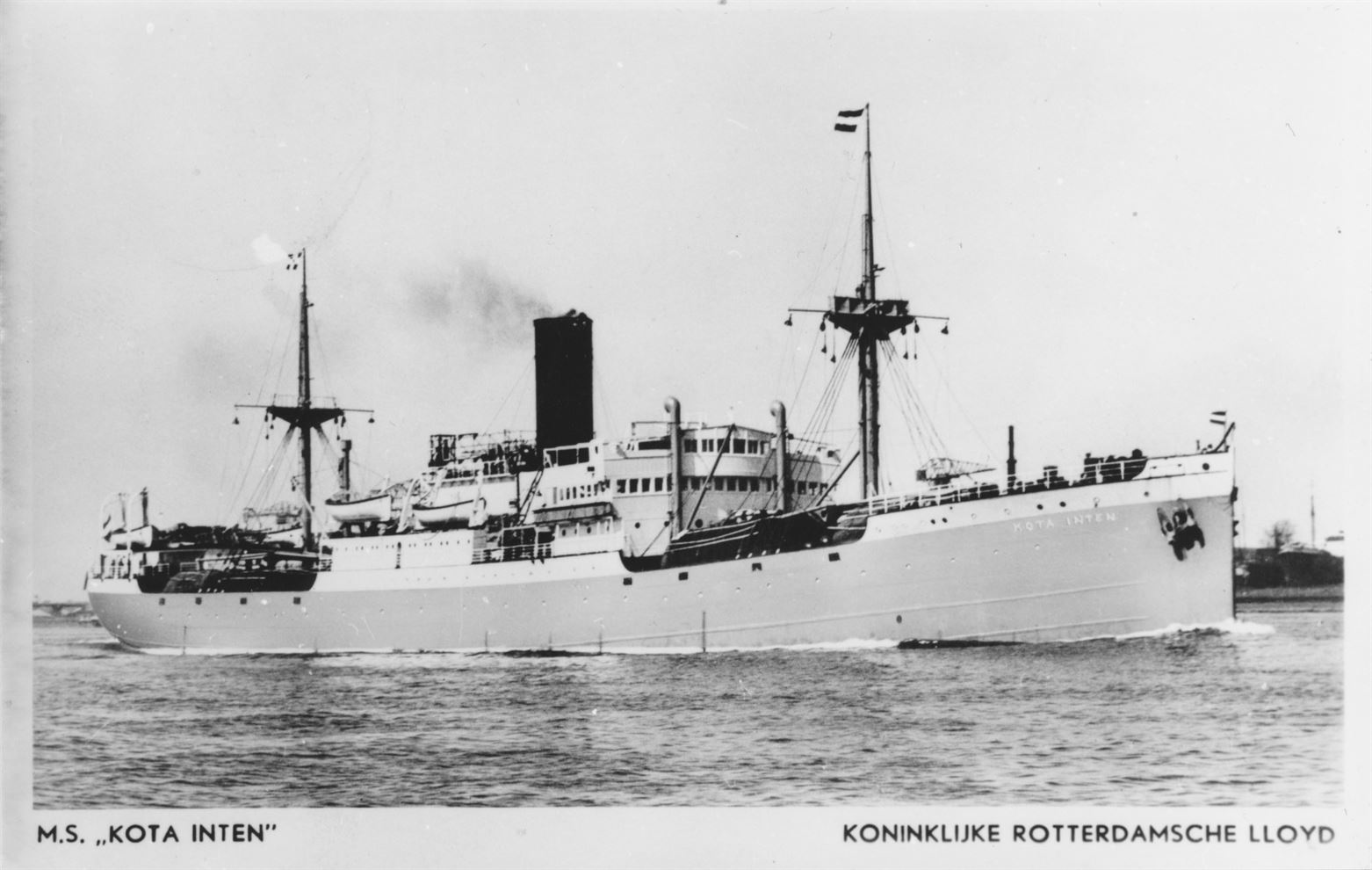

More than 12,000 Moluccans departed to the Netherlands. In February 1951, the first group of Moluccan military with wives and children had boarded on the Kota Inten. To them, the Netherlands was an unknown country, which they only knew from booklets they had read on the Dutch school (Hollandse school), or from the songs they had learned. Sam Saptenno, then ten years old, was one of the children who came to the Netherlands.

‘I had never been on a ship that big before. Naturally, that was an incredible experience for me. The toilets were equipped with toilet paper rolls, and we didn’t know those. We unrolled them at the back of the ship and at the propellers you would see the way the water hit, and then we let them go. Beautiful! I also often went to stand at the bow to watch the dolphins.’