Second World War

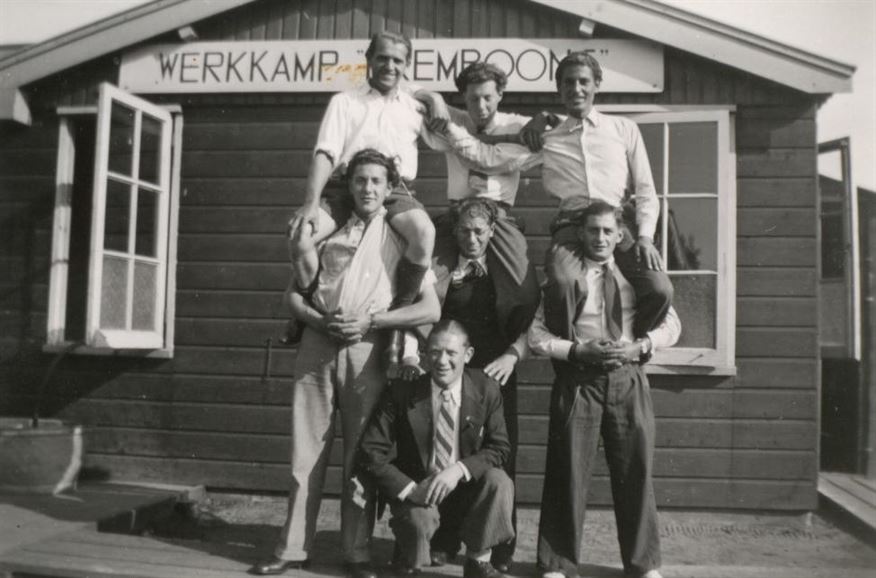

During the Second World War, Camp Westerbork was known as the 'gateway to hell'. It was a transit camp to concentration camps like Auschwitz and Sobibor. However, in 1939, the camp was initially built and used as a refugee camp.